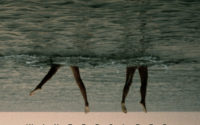

Sarah McLachlan’s ‘Surfacing’

My hopeless romantic streak started young—we’re talking second grade—so by the time I turned 12, I was well-versed in the high drama of longing. I’d had a series of largely unrequited crushes (alas, I never seemed to like the boys who liked me) and I thought I knew a thing or two about obstructed desire.

For a tenderhearted preteen in the late ’90s, Sarah McLachlan’s album Surfacing provided a potent exemplar of yearning with a capital Y. With her velvet-voiced declarations, she painted an enigmatic world of love in the shadows. In my last years of junior high, I played the CD repeatedly on my prized Aiwa boombox, so much so that it came to define that fleeting, angsty period when life was more becoming than being.

To this day, I melt when I hear “Do What You Have To Do.” Oh, how I once believed I already knew about that kind of tangled love. When I first heard the track, it satisfied some shard of my soul more satisfied with tempestuous love affairs than anything easily won. I’ve always wondered if I haven’t fully grown past that outlook, instead continuing to select relationships that hurt because somehow that feels better, or at least more familiar, than anything less stormy.

The song has a palpable heft thanks to the opening grand piano and the melancholy cello that later joins it. McLachlan’s voice, normally an atmospheric mezzo-soprano, dips as well, aiming for something earthier. “I’m ever swiftly moving/ Trying to escape this desire,” she sings about being connected to a fraught love she can’t relinquish. “The yearning to be near you/ I do what I have to do.”

The chorus is all riveting descension, as she crests above the current only to be pulled back under. “And I have the sense to recognize,” she sings, lifting her voice to its highest point on “sense,” before finding a plateau on “to recognize,” and then sinking once more. “I don’t know how to let you go,” she sings before two piano chords, in quick succession, punctuate the end of her thought.

My views on love have changed since those early days, but when I hear “Do What You Have To Do,” some echo of that 12-year-old persists and I’m immediately back in my small corner room with the twin bed and the peach bedspread, dreaming of a love powerful enough to capsize me.

For the longest time, I stopped listening to Surfacing. It called to mind the image of who I used to be and what I used to believe at that age—a piece that sat itchily and uneasily below the surface. But two years ago, I bought a copy on vinyl and fell through the tracklist like Alice returning to Wonderland. I couldn’t get over how I remembered every word even though I hadn’t sung along to those songs in over a decade.

Joan Didion said it best in Slouching Towards Bethelem: “I think we are well-advised to keep on nodding terms with the people we used to be, whether we find them attractive company or not. Otherwise, they turn up unannounced and surprise us, come hammering on the mind’s door at 4 a.m. of a bad night and demand to know who deserted them, who betrayed them, who is going to make amends.” I’ve not been kind to that 12-year-old. I’ve judged her too harshly for not knowing what it would take years to figure out.

Now, when I listen to Surfacing, I realize there’s space for all of those threads: the young, the naive, the hopeful and going to get hurt because of it. I wouldn’t be stitched into the person I am now without them.